The Global Food Crisis: Eating is a Political Decision

an interview with Adam Drucker

Dr. Adam G. Drucker is a Principal (Ecological) Economist with the Alliance of Bioversity International - CIAT and coordinator of a global program related to the “Economics of Agrobiodiversity Conservation and Use.” He has been involved in a wide range of natural resource management issues including: sustainable agriculture and rural development, deforestation, biodiversity conservation, water pollution, climate change, environmental policy development and the use of market-based instruments; and has held a number of positions in Latin America, Africa and Australia with the United Nations, national governments, international NGOs, the University of London and the Dept. for International Development (DFID/UK), the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI) and Charles Darwin University, Australia.

The statements in the following interview reflect Dr. Drucker’s personal opinions, and should not be taken to necessarily represent the viewpoints of any of the organizations he is, or has been, associated with.

IR: ”We face an unprecedented global hunger crisis," UN Secretary-General António Guterres warned in late June. "No country will be immune to the social and economic repercussions of such a catastrophe."

The immediate causes are obvious: Russia’s war with Ukraine along with COVID-19, conflict, and climate. The last of these looms ever larger, with dramatic warnings of forthcoming, or ongoing, mass extinctions of animals, marine life, insects, tree species and plants.

According to the UN’s Convention on Biological Diversity, the diversity of genes, species and ecosystems, are essential to making agricultural production and livelihood more resilient to shocks and stresses. This is especially important in the context of climate change. And yet, as we speak, humanity is dependent on fewer and fewer species to feed itself. In all of human history, around 7000 plant species that have been cultivated for food. Today, 3 crops account for 60% of global calorie intake. Twelve —along with 5 animal species— account for 75% of the world’s food.

On the food production side as well, extreme concentration and standardization has reduced the diversity of entities, production methods, and practices that produce the world’s food. We know that biodiversity is essential in the medium to long run, but we are increasingly dependent on agro-industrial practices and the monoculture of crops to feed the world in the short run.

Are we running full speed down a blind alley? Is there another green revolution around the bend that will save the day?

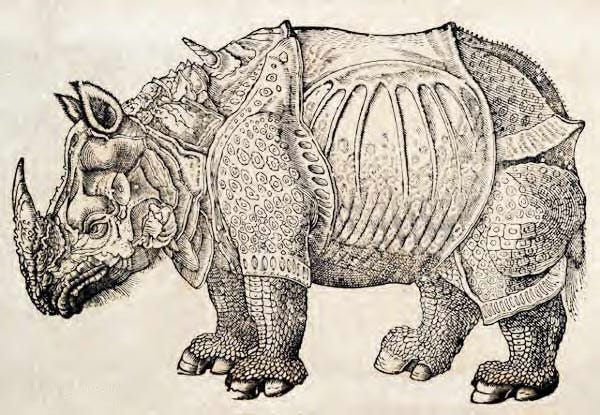

AD: When we talk about the conservation of biodiversity, people often think about charismatic megafauna such as tigers, pandas and whales, and through their donations to NGOs and others they show a significant willingness to pay for their conservation. The loss of diversity in agriculture is much less appreciated and receives much less support, which is ironic as humans don’t depend on tigers and pandas as a food source.

Did you know that there are thousands of varieties of potato and quinoa in Peru alone, yet we only find half a dozen in our supermarket? Of the thousands of apple varieties that existed in 19th Century America, perhaps only 100 commercial varieties now exist. The consequences of a food system that depends on a narrow range of varieties and species is not only risky in the medium and long terms but can also have severe short-term consequences. Think of the Irish potato famine in the mid-1800s, which was the result of a single potato variety being susceptible to blight, the consequences of which were over a million deaths due to starvation and a further 1.5 million people having to emigrate.

Potential consequences arising from a lack of diversity in agriculture are not confined to the distant past. Even today emerging pests and diseases, such as wheat rust or banana wilt could take a severe toll on globally important food crops. About a fifth of the world’s livestock breeds are also considered to be at risk of extinction. And while we might be better placed now than in the 1800s to address such challenges, thanks to advances in scientific understanding, breeding technologies and the availability of ex situ materials in genebank collections, the latter are limited to certain crops, and the unprecedented loss of diversity from farmers’ fields means that we have less weapons at our disposal to meeting an increasing range of challenges, including from climate change.

I like to think of agrobiodiversity like a deck of cards. There are different suits, colors and numbers, which allow us to play thousands of different games (canasta was always a favorite in my family). And while not all games require all the cards in the deck, so that losing a few cards might not seem that serious at first, as we lose more and more the number of games we can play diminishes drastically, especially when we may also not know which cards we have lost. Similarly, each loss of a variety or breed may result in our being less able to respond to new climate and emerging pest and disease challenges and so the need to ensure that we manage to keep as many of our diverse resources as possible.

While the green revolution, based on plant breeding for specific characteristics – such as high outputs— and the transition to large-scale monocultures permitted significant increases in yield to be achieved and economies of scale to be captured, thereby improving food security for hundreds of millions of people, it has also brought with it significant environmental impacts. For example, through its dependence on chemical fertilizers, high water use, mechanization leading to soil compaction, loss of hedgerows for wildlife and, of course, a displacement of many traditional varieties and livestock breeds that were considered “inferior” to these new “improved” (i.e. highly selected/intensively bred) varieties.

Yet many traditional varieties also have important characteristics, such as the ability to survive drought or grow on the marginal lands of the type that are associated with many poor smallholder farmers; or with regard to their taste and nutritional qualities (for example high iron content, important in the fight against anemia). The value of that diversity is increasingly being recognized and could indeed form the basis for a new green revolution.

IR: What are some of the consequences of concentration and the industrialization of food production?

AD: In addition to the risks involved in overly depending on a limited range of crops and within those crops a limited range of varieties, the concentration and industrialization of food production has contributed to unhealthy consumption patterns – witness the global obesity epidemic. Globally the number of obese people has tripled since 1975, according to the World Health Organization. Some people are even both obese and malnourished at the same time, given not only the quantity of the food they are eating, but also its quality – lacking in essential vitamins and micronutrients.

There is also a cultural impact. Traditional foods and food-related culture are lost. A community leader in Ecuador once told me “Eating is a political decision”, lamenting the food choices that younger generations were making, preferring “super-size me” fast foods over traditional more healthy dishes and the loss of the varieties that were now no longer in demand because of such changed preferences.

IR: Given the global food demands, is it irresponsible to use limited fertile lands for tree planting and re-wilding, and promoting lower-yield farming?

AD: There are certainly increasingly tough trade-offs to be made, as we have also seen in recent years with the production of ethanol for fuel instead of using such land for foods crops, and the consequent rise in some food prices. I think the answer lies in letting markets allocate scare resources efficiently, whether that is for food production, carbon sequestration or biodiversity conservation. But we cannot expect markets to necessarily reach an optimal and sustainable outcome on their own (this is one of the big differences between conventional economists and ecological economists). For example, if the reproduction rate of a certain fish stock is below the interest rate at the bank, it would be more profitable to fish to extinction and put the proceeds in the bank —financially rational but ecologically stupid. Extinction is forever while conventional economics assumes we can instead move smoothly up and down supply and demand curves and furthermore not encounter any thresholds beyond which a point of no return is ever reached.

Sustainability constraints instead need to be established (to address scale issues) and then the market can be used to address how given stocks or capacity can be allocated in the most efficient way. So fertile lands, less fertile lands and those more suited for forestry or re-wilding should have values associated with them that fully reflect their different economic (including social and environmental) values. Unfortunately, not only are there a lack of sustainability constraints, but also there are all kinds of perverse subsidies that undermine the price mechanism’s ability to fully reflect actual values. For example, OECD countries spend something like USD260 billion a year on agricultural subsidies, mostly to the conventional farming sector, thus providing a huge bias against potentially more sustainable activities.

IR: Is organic farming environmentally sustainable?

AD: Organic farming may be more sustainable in certain ways, for example with regard to its use of fertilizers or in terms of its impact on soil or water quality. But there are always trade-offs to be considered. For example, lower yields may require more land to be farmed and where this results in conversion of forested or wildlands, its environmental benefits would be reduced. The length of organic produce market chains may also be a concern. Relative to locally-produced non-organic food products, where more labor-intensive organic foods are being flown in from other countries where labor is cheaper, this may well result in a higher carbon footprint; as can shorter shelf life (given less post-harvest treatments) and thus higher levels of food waste.

IR: Food production is a response to changing eating habits and preferences. Is there a way to reintroduce and revalue diversity of tastes and diets?

AD: One thing we have been working on is a “Feed Me Sustainably” decision-support tool that could be used by public food procurement programs (such as those involved in providing school meals) with which to assess and seek to mitigate the environmental impacts of their purchasing decisions, such as with regard to carbon emissions, chemical fertilizer use, soil/water quality, agrobiodiversity and packaging waste. Such programs feed millions of children every day across the world and provide an excellent opportunity to instead buy more locally, support smallholder farmers and generate a sustainable demand for threatened traditional varieties with important nutritional characteristics. Along with educational and dietary benefits, they would also re-introduce children to more traditional and culturally appropriate meals, something that might have a life-long impact.

Besides schools there are also many other public institutions whose food purchases could make a big difference, such as universities, hospitals and the armed forces.

IR: One of the unintended consequences of fish hatcheries, according to critics, is that it functions to reverse natural selection --in effect giving the edge to less fit species. Is this not also the case with food crops?

AD: I think it’s useful to think of different crop varieties and livestock breeds as different technologies that are appropriate in different contexts; the same way that a Ferrari might be just the right car for driving on the autobahn, but a Land Rover will be the technological choice better-suited for off-road driving. The challenge then is to make the right technology choice for any given production environment.

There is also a production-risk trade-off to be made. So while a uniform improved crop variety might produce a lot in good years, it may fail completely in poor climatic years; while a more traditional and usually less uniform variety might never produce as much, it may always produce at least something whatever the weather. For poor smallholder farmers who would otherwise starve to death in the face of a complete crop failure, such down-side risk minimization may well be more important than maximizing output. So “fitness” is to some extent in the eye of the sower.

But while farmers may make their own individual decisions, collectively that could result in a lack of resilience at the landscape level – back to the Irish potato famine example – and governments need to guard against this by rewarding at least a minimum number of farmers for maintaining diversity for the public good and thus compensating them for any opportunity costs incurred by not only planting so-called improved varieties. Hence, we have been working hard both to help governments define conservation goals (not only to decide what to board onto Noah’s Ark but also how much – i.e. what proportion of overall farmland dedicated to diverse production might be considered a “safe minimum standard”) and to provide an incentive mechanism for them to do so – called Payments for Agrobiodiversity Conservation Services. You can see a short video about its application to quinoa diversity in Peru here.

IR: Will we be able to feed ourselves in 5 years? in 30?

AD: There is currently no food shortage in the world. Rather its distribution is uneven, so that some have access to too much food and others to not enough. There is also a huge amount of food waste (from post-harvest losses to unconsumed food discarded by affluent households), perhaps amounting to a third of what is produced. That also represents a huge waste of resources in terms of land, water and carbon emissions capacity. So despite the challenge of climate change, I believe that we can continue to feed the world, particularly if we don’t throw away all of the “cards” that we will need in order to be able to properly face that challenge.

However, the sustainability challenge more broadly is essentially about how many people consuming how much for how long. The elephant in the room (more charismatic megafauna) is the number of people on this planet - almost 8 billion now and expected to be close to 10 billion by 2050. When I was born there were just over 3 billion. And it certainly seems unlikely that everyone will be able to consume at current Western levels. We would need several more planet Earths for that to be possible. So while there is almost no discussion of the population issue, we can’t grow indefinitely on “Spaceship Planet Earth”, so ultimately a human population sustainability constraint will one day need to be established.

How to do that in a fair and equitable way will raise many ethical issues that humanity will need to grasp in the not too distant future.